Obesity and overweight…why are so many people increasingly struggling in their battle against the bulge? Is it hormones? Or our sedentary lifestyle thanks to modern conveniences?

Could it be our genes? Surely stress is to blame…! Pollution, carbs, wheat, pesticides, endocrine disruptors, those are the culprits! “Not enough protein.” “Not enough fat in the diet.” “I don’t eat enough, so that’s why my body holds onto calories.” “Metabolism.”

With so many varying opinions, it is essential to examine what the best current evidence has to say about overweight and obesity. In fact, there are many touting that obesity and overweight is not a problem at all, that it should be fully embraced as a norm.

While embracing the current state of overweight and obesity as a norm may make sense from a social comfort standpoint, does it also make sense from a population health standpoint? Is there something to the “healthy at any size” movement?

This article will examine the current evidence concerning obesity and overweight causes, health implications, and treatment option considerations.

The state of our nation: how many of us are obese and overweight?

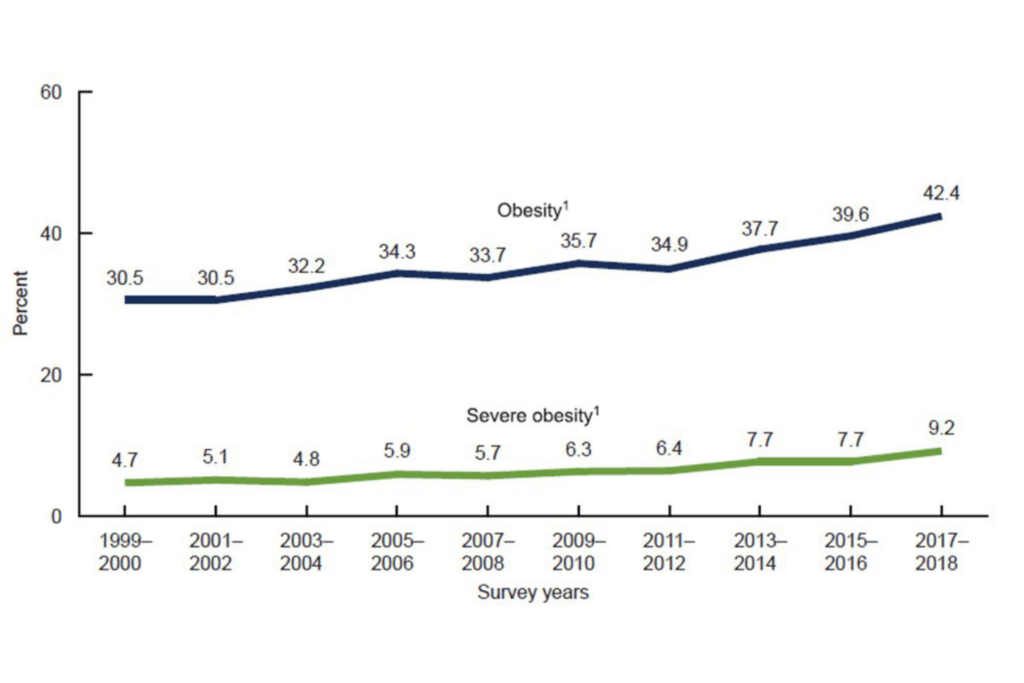

There is little dispute that the average American today weighs more than the average American 20 years ago. According to the CDC (2022a), obesity rates in America have soared to over 40%!

This means that nearly half of the nation’s population is obese. When you combine the percentages of Americans who are either overweight or obese, the number rises to approximately 73% (NIDDKD, 2021).

Nearly 1 in 10 Americans are now considered severely obese (NIDDKD, 2021).

Obesity trends in the United States

These trends show no signs of slowing. The cases of severe obesity have nearly doubled since the year 2000, from 4.7% of the population to 9.2% in 2018.

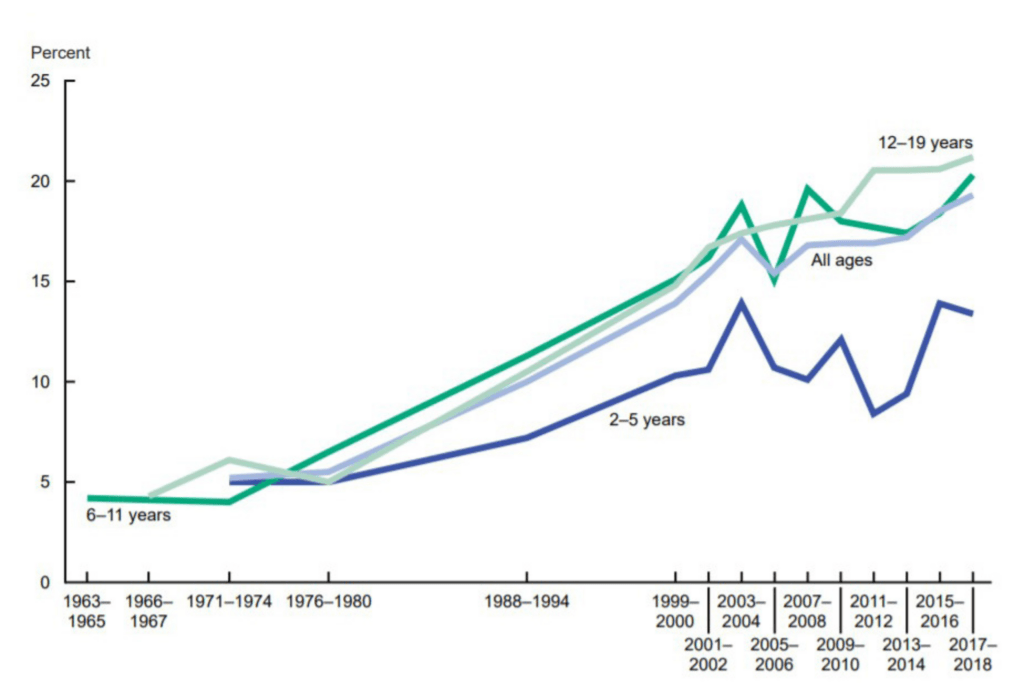

Youth obesity rates have skyrocketed for adolescents, with around 5% being obese in the 1970’s to nearly 20% as of 2018 (NIDDKD, 2021).

Are obesity rates impacted by race and socioeconomic status?

The CDC notes that obesity rates are highest for non-hispanic black adults, with a 49.9% obesity rate (CDC.gov, 2022a). This compares to approximately 46% of hispanic adults and 41% of white adults.

Asian Americans have the lowest rates of obesity, at approximately 16%. Overall, persons with a college degree level of education or higher have lower rates of obesity. Findings for obesity and earning status are inconsistent in terms of high earners versus those that are middle class across racial groups (CDC.gov, 2022a).

For example, among white and hispanics earning higher annual incomes, obesity occurred less frequently versus those in the lower earning groups. For blacks, those in the higher earning categories had higher rates of obesity versus blacks earning lower incomes (CDC.gov, 2022a).

How is overweight and obesity diagnosed?

Overweight and obesity diagnosis is made most typically based on a person’s body mass index (BMI). BMI factors in a person’s height and weight (CDC.gov, 2022c).

The Adult BMI Calculator allows you to enter your height and weight to determine your BMI. Another option is to find your height and weight on the BMI Index Chart.

As noted by the CDC (2022c):

- A BMI less than 18.5 is considered underweight

- A BMI between 18.5 and under 25 is considered healthy

- A BMI from 25 up to just under 30 is considered overweight

- When your BMI is 30.0 or higher, this is considered to be obese

Obesity is further broken into classifications depending on severity:

- Class 1 obesity: a BMI of 30 to just under 35

- Class 2 obesity: a BMI of 35 to just under 40

- Class 3 “severe” obesity: a BMI of 40 or greater

How useful is BMI anyway?

BMI criticisms

There are social criticisms of the use of BMI as a tool to measure and define obesity (Gutin, 2018). These critiques vary from BMI being a tool of racism to misclassify black women (Strings & Bacon, 2020), to BMI being a tool that serves to promote sameness in terms of aesthetics and body shape regardless of true impacts on health (Gutin, 2018).

A common example cited to negate the value of BMI as predictive of an unhealthy body composition is the example of body builders and elite athletes. Heavily muscled athletes who clearly have low body fat percentages may rate as overweight or obese on the BMI scale (Weir & Jan, 2022).

However, BMI is used currently as a population health tool (Gutin, 2018). Being that a very small percentage of the population have the muscular development and body fat percentages of elite athletes and bodybuilders, this criticism of BMI argues for the exception as opposed to the intent of current BMI usage.

BMI calculations have to be altered when calculating for Asian and South Asian populations as the standard BMI calculation may actually underestimate overweight and obesity rates in these populations (Weir & Jan, 2022).

Perhaps a more convincing argument for the limitations of BMI is the caution provided against using it as a sole measure of predicting health outcomes (Gutin, 2018).

Like any tool, BMI must be used in conjunction with other assessment criteria such as medical examinations, labwork/ diagnostics, socioeconomic factors, personal and family history, among other important data when evaluating individuals (Gutin, 2018; Strings & Bacon, 2020).

Elevated BMI and disease risk: what about being “healthy at any size?”

While imperfect in correctly predicting every case of metabolic health or disease, repeated and massive population health studies performed world wide have affirmed BMI’s ability to predict disease and premature death across population groups (Harvard T. Chan School of Public Health, 2016).

A review of 269 studies on the predictive ability of the BMI measure on death and disease rates was published in The Lancet in 2016 (Harvard T. Chan School of Public Health, 2016). These studies involved:

- More than 30 counties,

- More than 10 million study participants,

- Lasting an average study period of 14 years, and

- The various studies spanned 45 years of data collection overall (Harvard T. Chan School of Public Health, 2016).

After controlling for smoking and chronic disease at the time of participant enrollment, the analysis demonstrated:

- Lowest death rates occurred for participants with a BMI of 22.5 to less than 25

- An overweight BMI of 25-27.5 was associated with a 7% increase in rate of deaths

- An overweight BMI of 27.5 to just under 30 was associated with a 20% increase in death rates

- A class I obesity BMI of 30 to just under 35 was associated with a 45% increase in death rates

- A class II obesity BMI of 35 to just under 40 was associated with a 94% increase in death rates

- A class III obesity BMI of 40 and above was associated with a nearly 300% increase risk in death rates!!!

The same analysis published in The Lancet noted that for every 5 point increase in BMI over 25:

- Deaths from cardiovascular rose by 48%

- Deaths from respiratory disease rose by 38%

- Deaths from cancer rose by 19%

Chronic disease and overweight/ obesity

As noted above, death rates consistently increase for cancer, heart disease, and respiratory disease with increases in BMI. But what are the effects of BMI on developing long term chronic illnesses?

Overweight and obesity increases the risk of a variety of long term illnesses in both children and adults, such as (CDC, 2022b):

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- Sleep apnea

- Asthma

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Osteoarthritis, muscle and joint pain

- Gallbladder disease

- Depression and anxiety

- Stroke

- Increases in 13 types of cancer including thyroid, breast, colon, pancreas, kidney, blood, and others

- Subjection to bullying, low self esteem, stigmatization for children

The health risks and consequences of being overweight / or obese are no joke. It is a serious condition that takes a toll on the mind and body.

While not every person with overweight and obesity suffers every adverse outcome described above, decades of research affirms substantial increases in the above diseases and in premature death as our weight climbs above a healthy BMI. However…

Health improvements ARE possible at any size!

While increases in BMI can predict risks, significant improvements in health status and risk reduction are within reach even for persons who do not ever achieve a “healthy BMI.”

For example, a modest weight loss of 5% can result in significant improvements in a variety of health measures. Benefits increase as weight loss increases to 10% and 15%, even if the weight loss does not result in a person achieving their “ideal body weight” (Ryan & Yockey, 2017).

Examples of these improvements (Ryan & Yockey, 2017):

- At 5% body weight reduction: blood sugar levels and insulin sensitivity improve, fertility improvements occur for women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), and triglycerides are reduced.

- At 10% body weight reduction: insulin sensitivity in muscle tissue improves, HDL cholesterol begins to improve, there is a 21% reduction in serious cardiovascular event risk, liver clears itself of more than 50% of triglycerides, inflammation is reduced when paired with exercise, and knee pain is reduced.

- At 15% body weight reduction: c-reactive protein levels are reduced (c-reactive protein measures body wide inflammation), pancreas beta cell function improves (these produce insulin), and insulin sensitivity continues to improve. The liver further cleanses itself of triglycerides.

These are fantastic improvements in health status!

In fact, even if NO weight is lost, eating a nutritious healthy diet and exercising can improve insulin sensitivity, decrease cardiovascular disease risk, lower blood pressure, and lower inflammation (Gaesser, Angadi, & Sawyer, 2011).

So how did we get here?

Genetics alone do not explain the rapid population shift towards overweight and obesity. Over 50 genes have been identified that may contribute to obesity, but these tend to have small effects (CDC, 2013).

About 5-10% of the population carry specifically identified genes that are more significant promoters of obesity (Choquet& Meyre, 2011). However, the number of persons overweight and obese far exceed this percentage of the population.

What about hormones?

Many people are convinced that hormones are to blame for their struggles with obesity. Indeed, obesity is more prevalent in women than in men. However, obesity is prevalent across sexes at higher rates than in history (Leeners et al., 2017).

Estrogen has favorable effects on body fat distribution in women, reducing fat deposits in the dangerous visceral regions while favoring distribution in the thighs and buttocks. This protection wanes after menopause (Leeners et al., 2017). Also, effects of estrogen on fat distribution vary widely by individuals (Leeners et al., 2017).

Progesterone has been associated with increased eating and increased binging during the luteal phase of a female’s 28-day cycle (days 15-28) (Leeners et al., 2017). Estrogen on the other hand decreases food intake during the follicular phase.

Women are more susceptible to binge eating behaviors and this is believed to be due to both progesterone and its interplay with genetics, particular in persons with specific genetic mutations (Leeners et al., 2017).

Does Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) cause obesity?

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) is a common condition affecting approximately 5-13% of females (Bednarska & Siejka, 2017). PCOS is commonly associated with insulin resistance, high cholesterol, overweight/ obesity, and increased risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Researchers note that it is difficult to separate the cause and effects of PCOS (Bednarska & Siejka, 2017). For example, high levels of insulin and inflammation (such as from overeating/ poor/ pro-inflammatory diet) seem to exacerbate PCOS, and losing weight significantly improves PCOS symptoms.

Genes increase risk of developing PCOS (Bednarska & Siejka, 2017). However, research has demonstrated that reducing meat intake, boiling and steaming foods as opposed to frying and roasting them, and reducing intake of processed foods and sugar significantly improve PCOS symptoms and pathology (Gregor, 2017).

It is unclear that PCOS causes obesity, however, it is clear that losing weight and eating a mostly plant-based diet consisting of minimally processed foods improve PCOS symptoms (Bednarska & Siejka, 2017; Gregor, 2017).

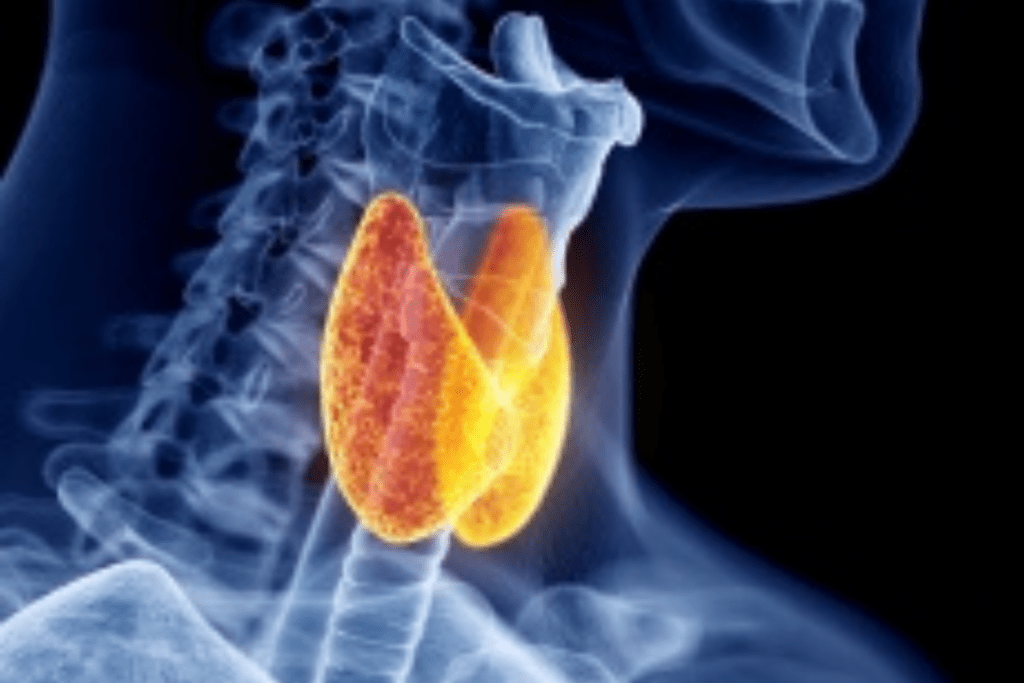

Is it my thyroid?

Other hormones commonly associated with obesity are thyroid hormones (Walczak, & Sieminska, 2021). It is noted that even mild hypothyroidism can slow the resting metabolic rate.

Even minor changes in the resting metabolic rate can lead to significant increases in weight over time (Walczak & Sieminska, 2021).

However, the relationship between insufficient thyroid function and obesity is not necessarily one of cause and effect. Specifically, poor diets consisting of refined carbohydrates and high fat intake, along with excess fat tissue can themselves impair thyroid function (Walczak & Sieminska, 2021).

So did poor thyroid function cause obesity, or did the poor diet and obesity cause inflammation and impairment of the thyroid gland, leading to further weight gain? Research suggests that in many cases, it is the latter (Walczak & Sieminska, 2021).

Genes and hormones cannot alone explain the sudden rise in obesity

Instead of genetics or hormones fully explaining the rapid rise in overweight and obesity, the interplay of genes and hormones with a change in our environment provides the best explanation (CDC, 2013).

Specifically, our environment is what has changed rather than our genes in the last several decades. Indeed our current living, recreational, and working environments strongly promote overweight and obesity (Hall & Kahan, 2018).

Is our local environment making us overweight and obese?

One of the most significant driving factors in our nation’s skyrocketing overweight and obesity rates can be explained by our ready access to low nutritional quality, calorie dense ultra-processed foods (Hall & Kahan, 2018).

Examples of ultra-processed foods include: (The Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, 2022).:

- Soda and soft drinks,

- Chips, crackers, and similar snack foods

- Chocolate,

- Candy

- Donuts, bagels, muffins, cake, cookies

- Ice-Cream,

- Sweetened Breakfast Cereals,

- Packaged Soups,

- Chicken Nuggets,

- Hotdogs, lunch meats, burgers

- Fries and other fast food items

- The list goes on and on…

These foods are high in calories, sugar, salt, and fat, while low in natural fiber, vitamins, nutrients, antioxidants, and water (Ahima, 2009).

The sugar, salt, and fat concentrated in ultra-processed foods stimulate the dopamine and opioid receptors in our brains, making us want to eat more and more.

Ultra-processed foods are also often brightly colored with food dyes/ or packaged in bright packaging to make them appear more enticing (Ahima, 2009). These foods hijack our senses, leading us to choose them again and again.

Convenience, but at the cost of our health and waistlines?

On average, Americans consume more than half their food intake from sources such as restaurants, takeout orders, cafes, or food otherwise prepared outside the home (Bleich et al., 2020).

One in 3 Americans eats fast food daily (Bleich et al., 2020).

For every meal consumed away from home per week on average, there is a corresponding predictable increase in a person’s BMI (Bhutani et al., 2018).

In other words, eating foods prepared outside of the home routinely is a reliable predictor of overweight and obesity (Bhutani et al., 2018).

Combined with our sedentary forms of entertainment, work, and transportation, it is little surprise that the surge in consumption of ultra-processed and fast foods prepared away from home is causing so many of us to pack on the pounds (Hall & Kahan, 2018).

Our appetites surge and metabolism slows after weight loss!

It may feel disappointing to learn that when we lose weight, our appetite surges ABOVE our prior levels to encourage us to regain the weight (Hall & Kahan, 2018). In fact, for every 2.2lbs of weight lost, our appetite increases by 100 calories above our prior levels.

Our bodies were designed to protect us against starvation, not over-abundance.

Further, when we lose weight, our metabolism actually slows! (Hall & Kahan, 2018). This is because it takes less calories to support and move a smaller, lighter body.

It is not surprising then that with a slower metabolism AND a surge in appetite along with immersion in an obesogenic environment, people frequently regain all the weight they lost following a weight loss endeavor (Hall & Kahan, 2018).

Weight loss & maintenance: think short term AND long term!

For people interested in losing weight, the research is clear that weight loss and weight maintenance require long term strategies (Hall & Kahan, 2018). Indeed, experts now consider overweight and obesity a chronic disease (Garvey, 2022).

As a chronic disease, treatments involving multiple approaches and health care disciplines over time for best outcomes is essential (Hall & Kahan, 2018; Garvey, 2022).

Strategies for optimizing long term weight loss and long term management include a combination of the following (Hall & Kahan, 2018):

- Long term medical and / or group support: even effective short term weight loss interventions are unlikely to be sustained long term if there is not a longer term support system in place–lasting for at least a year. Ongoing support from healthcare providers or support groups for at least one year is a proven strategy to reduce the risk of significant weight regain.

- Behavioral / lifestyle strategies such as self-monitoring, movement/ exercise, portion control, eating breakfast consistently, eating more fruits and vegetables, among other interventions.

- Mindset strategies such as celebrating various successes when weight loss has shifted into weight maintenance phase. Successes shift from the scale moving to improvements in lab work, clinical measures such as blood pressure, heart rate, etc.

- Relapse prevention strategies: anticipating relapse high risk situations, developing individualized strategies to cope with temptations as well as relapses is critical.

- Cognitive restructuring and cognitive flexibility strategies to shift thinking away from “all or nothing” “I’m a failure” and other negative rigid thought patterns towards patterns of adaptation and recovery after a setback are key for long term success.

- Identification of values can help sustain an individual when motivation waxes or wanes. Understanding how maintaining a lower weight serves greater values and goals in life can assist in overcoming setbacks.

Weight loss interventions & realistic expectations

Significant weight loss is possible and can be achieved long term. However, having realistic expectations from the start means less disappointment and discouragement during a journey that requires long term commitment.

Natural Weight loss: how much can I expect to lose with diet and exercise?

The CDC (2022d) notes that 1 to 2 lbs per week is realistic for natural, safe weight loss. That means even if you only have four pounds lost in a month, you are still on target for natural weight loss.

This may seem small, but spread over 12 months, this is nearly 50 lbs.

Further, many overweight and obese individuals set unrealistic goals for themselves, such as a goal of losing 20 to 30% of their body weight. For most individuals, 5-15% is a more realistic goal (Severin et al., 2019).

This is important, as just losing 5-10% of body weight can lead to substantial health improvements (CDC, 2022d).

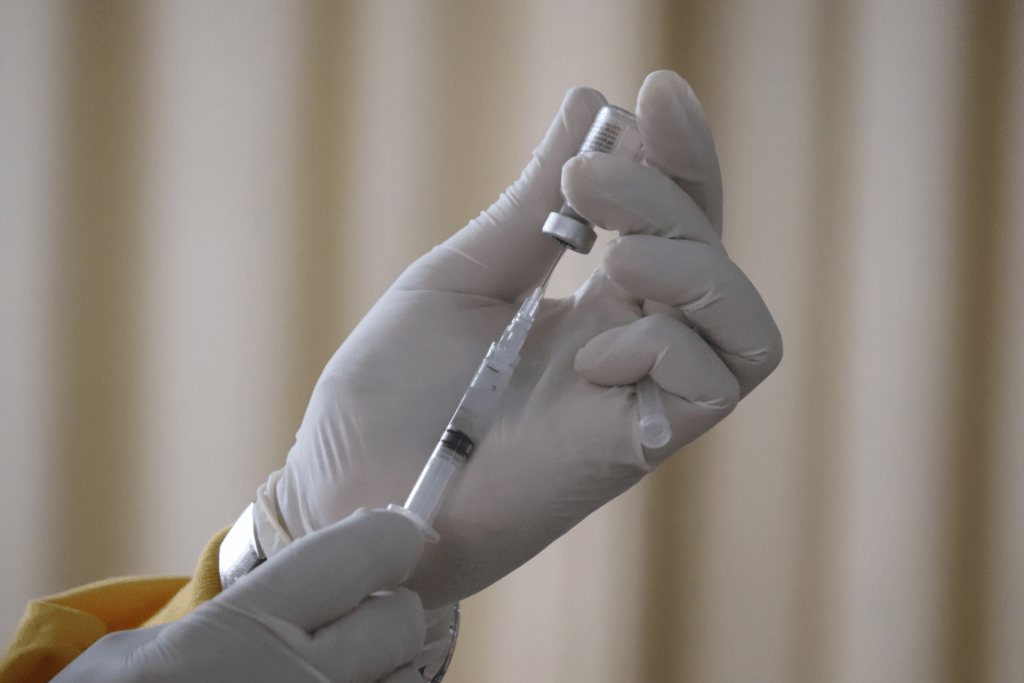

Will weight loss medications enhance my results?

FDA approved weight loss medications consist of the oral medications orlistat, lorcaserin, phentermine/topiramate, naltrexone/bupropion, and liraglutide (Severin et al., 2019). These medications can produce an additional 3% to 10% body weight reduction in the course of a year.

Newer injectable medications are showing promise, though several commonly used lack FDA approval currently for weight loss. Tirzepatide, for example, has produced a 20% body weight loss in human clinical trials over a period of 72 weeks involving diabetic participants (Chavda et al., 2022).

Similarly, the use of semaglutide injections during a 68 week trial period led to an average weight loss of 18.5% from the participants’ original body weight (Rubino et al., 2022).

While the newer weight loss medications have proven more effective than older medications, they are frequently not covered by insurance (Dunn, 2022). At costs over $1000.00 per month, few patients can afford to pay for these medications out of pocket for ongoing durations.

Further, without meaningful lifestyle changes, dependence on medications to sustain any weight loss achieved is inevitable. Stop the medications? Regain the weight–unless you have adopted sufficient exercise/ movement and nutritional strategies during the weight loss journey.

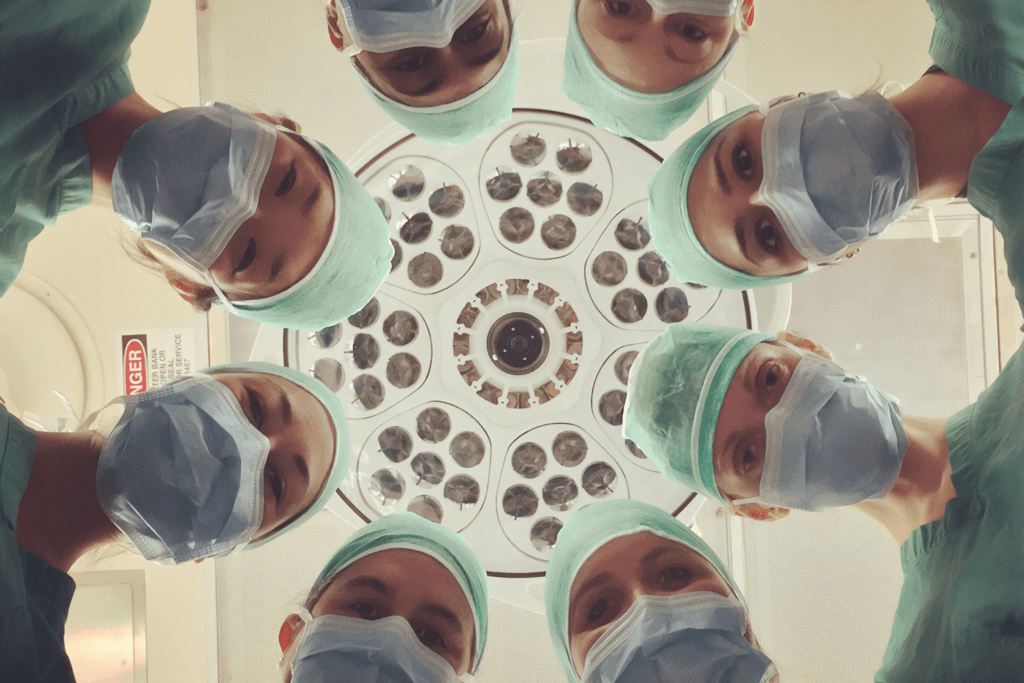

What about bariatric surgery?

Bariatric surgery is indicated for persons with a BMI over 40, or for those with a BMI over 35 plus obesity related disease processes, after lifestyle and medicine approaches have failed (Severin et al., 2019).

The most common procedures are the Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) and Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy (LSG). These surgical procedures commonly produce 60% or more reductions in body weight within 1 year (Severin et al., 2019).

Many patients continue to lose weight for up to12 years postoperatively. Patients experience improvements in diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol (Severin et al., 2019). Patients also experience lower cancer incidence and mortality following bariatric surgery on average compared to obese patients who do not get the surgery and remain obese (Aminian et al., 2022).

However, weight regain is still possible, and not all patients experience such high degrees of weight loss post surgery. In fact, up to 1 in 4 patients regain all their weight after bariatric surgery within 10 years (UCLA Health, 2023).

Most patients regain at least 30% of their lost weight in 10 years following bariatric surgery (UCLA Health, 2023).

Activity patterns, psychological factors, and improper nutrition are all factors that can undermine results in bariatric surgery (Severin et al., 2019). As such, a recurring theme as research on obesity accumulates is that proper nutrition and exercise are cornerstones of successful prevention and treatment, even if medical therapies are utilized to support weight loss efforts.

Summary

Overweight and obesity continue to increase in the United States at a dramatic pace. This pace is too fast to be explained simply by changes in hormones or genetics.

While genetics and hormones may play a role in who is more likely to become overweight or obese, it is clear what has changed the most since the 1970’s to fuel the epidemic is our food and social environment.

Highly processed foods such as chips, muffins, cookies, fast food, foods prepared away from home, candy, donuts, bagels, restaurant foods, cafe foods–these foods are more affordable, more accessible, and more highly consumed than ever before.

The health implications and costs of overweight and obesity are well known and established.

Treatment plans require short term and long term strategies. Medical therapies are research-backed to enhance weight loss, but lifestyle changes such as diet and exercise are critical for lasting success. Without substantial changes to our food and social environments, obesity and overweight is likely to continue its unprecedented climb.

References

Ahima R. S. (2009). The end of overeating: Taking control of the insatiable American appetite. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 119(10), 2867. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI40983

Aminian, A., Wilson, R., Al-Kurd, A., Tu, C., Milinovich, A., Kroh, M., Rosenthal, R. J., Brethauer, S. A., Schauer, P. R., Kattan, M. W., Brown, J. C., Berger, N. A., Abraham, J., & Nissen, S. E. (2022). Association of Bariatric Surgery With Cancer Risk and Mortality in Adults With Obesity. JAMA, 327(24), 2423–2433. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.9009

Bednarska, S., & Siejka, A. (2017). The pathogenesis and treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: What’s new?. Advances in clinical and experimental medicine : official organ Wroclaw Medical University, 26(2), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.17219/acem/59380

Bhutani, S., Schoeller, D. A., Walsh, M. C., & McWilliams, C. (2018). Frequency of Eating Out at Both Fast-Food and Sit-Down Restaurants Was Associated With High Body Mass Index in Non-Large Metropolitan Communities in Midwest. American journal of health promotion : AJHP, 32(1), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117116660772

Bhutani, S., Schoeller, D. A., Walsh, M. C., & McWilliams, C. (2018). Frequency of Eating Out at Both Fast-Food and Sit-Down Restaurants Was Associated With High Body Mass Index in Non-Large Metropolitan Communities in Midwest. American journal of health promotion : AJHP, 32(1), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117116660772

Bleich, S. N., Soto, M. J., Dunn, C. G., Moran, A. J., & Block, J. P. (2020). Calorie and nutrient trends in large U.S. chain restaurants, 2012-2018. PloS one, 15(2), e0228891. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228891

CDC.gov. (2022a). Adult obesity facts. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html

CDC.gov (2022b). Consequences of obesity. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/consequences.html

CDC.gov. (2022c). Defining adult overweight and obesity. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html

CDC.gov. (2013). Genes and obesity. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/resources/diseases/obesity/obesedit.htm#:~:text=So%20far%2C%20rare%20variants%20in,most%20with%20very%20small%20effects.

CDC.gov. (2022d). Losing weight. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/losing_weight/index.html#:~:text=When%20you’re%20trying%20to,to%20keep%20the%20weight%20off.

Chavda, V. P., Ajabiya, J., Teli, D., Bojarska, J., & Apostolopoulos, V. (2022). Tirzepatide, a New Era of Dual-Targeted Treatment for Diabetes and Obesity: A Mini-Review. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 27(13), 4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27134315

Choquet, H., & Meyre, D. (2011). Genetics of Obesity: What have we Learned?. Current genomics, 12(3), 169–179. https://doi.org/10.2174/138920211795677895

Dunn, L. (2022). New weight loss drugs are highly effective, so why aren’t they widely used? Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/new-weight-loss-drugs-effective-insurance-coverage-shortage-rcna32781

Gaesser, G. A., Angadi, S. S., & Sawyer, B. J. (2011). Exercise and diet, independent of weight loss, improve cardiometabolic risk profile in overweight and obese individuals. The Physician and sportsmedicine, 39(2), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.3810/psm.2011.05.1898

Garvey W. T. (2022). Is Obesity or Adiposity-Based Chronic Disease Curable: The Set Point Theory, the Environment, and Second-Generation Medications. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, 28(2), 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eprac.2021.11.082

Gregor, M. (2017). Best foods for polycystic ovary syndrome. Retrieved from https://nutritionfacts.org/video/best-foods-for-polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos/

Gutin I. (2018). In BMI We Trust: Reframing the Body Mass Index as a Measure of Health. Social theory & health : STH, 16(3), 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-017-0055-0

Harvard T. Chan School of Public Health. (2016). As overweight and obesity increase, so does risk of dying prematurely. Retrieved from https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/press-releases/overweight-obesity-mortality-risk/

Hall, K. D., & Kahan, S. (2018). Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity. The Medical clinics of North America, 102(1), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.012

The Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. (2022). What is ultra-processed food and how can you eat less of it? Retrieved from https://www.heartandstroke.ca/articles/what-is-ultra-processed-food#:~:text=These%20foods%20go%20through%20multiple,%2C%20hotdogs%2C%20fries%20and%20more.

Leeners, B., Geary, N., Tobler, P. N., & Asarian, L. (2017). Ovarian hormones and obesity. Human reproduction update, 23(3), 300–321. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmw045

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDKD). (2021). Overweight & obesity statistics. Retrieved from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/adult-overweight-obesity/definition-facts

Rubino, D. M., Greenway, F. L., Khalid, U., O’Neil, P. M., Rosenstock, J., Sørrig, R., Wadden, T. A., Wizert, A., Garvey, W. T., & STEP 8 Investigators (2022). Effect of Weekly Subcutaneous Semaglutide vs Daily Liraglutide on Body Weight in Adults With Overweight or Obesity Without Diabetes: The STEP 8 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA, 327(2), 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.23619

Ryan, D. H., & Yockey, S. R. (2017). Weight Loss and Improvement in Comorbidity: Differences at 5%, 10%, 15%, and Over. Current obesity reports, 6(2), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-017-0262-y

Severin, R., Sabbahi, A., Mahmoud, A. M., Arena, R., & Phillips, S. A. (2019). Precision Medicine in Weight Loss and Healthy Living. Progress in cardiovascular diseases, 62(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2018.12.012

Strings, S., & Bacon, L. (2020). Prescribing weight loss to Black women ignores barriers to their health. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-racist-roots-of-fighting-obesity2/

Walczak, K., & Sieminska, L. (2021). Obesity and Thyroid Axis. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(18), 9434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189434

Weir, C. B., & Jan, A. (2022). BMI Classification Percentile And Cut Off Points. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31082114/